“Sometimes it is the people no one imagines anything of who do the things no one can imagine.”

“Sometimes it is the people no one imagines anything of who do the things no one can imagine.”

And so – as this tagline of the brilliant movie, The Imitation Game, describes – it was with Alan Turing, the man who was abnormal, who was different, who no one imagined anything of.

This man, it turns out, was responsible for shortening the Second World War by two years and for the saving of 14 million lives. How’s that for a boast when you get to the Pearly Gates?! (never mind some suspect theology behind that last statement, but I think you get what I’m trying to say).

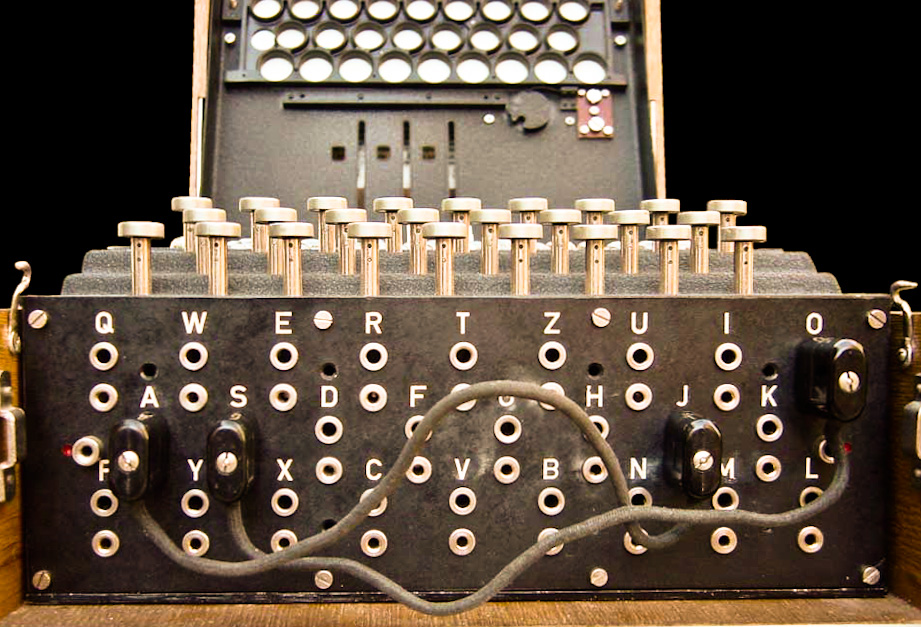

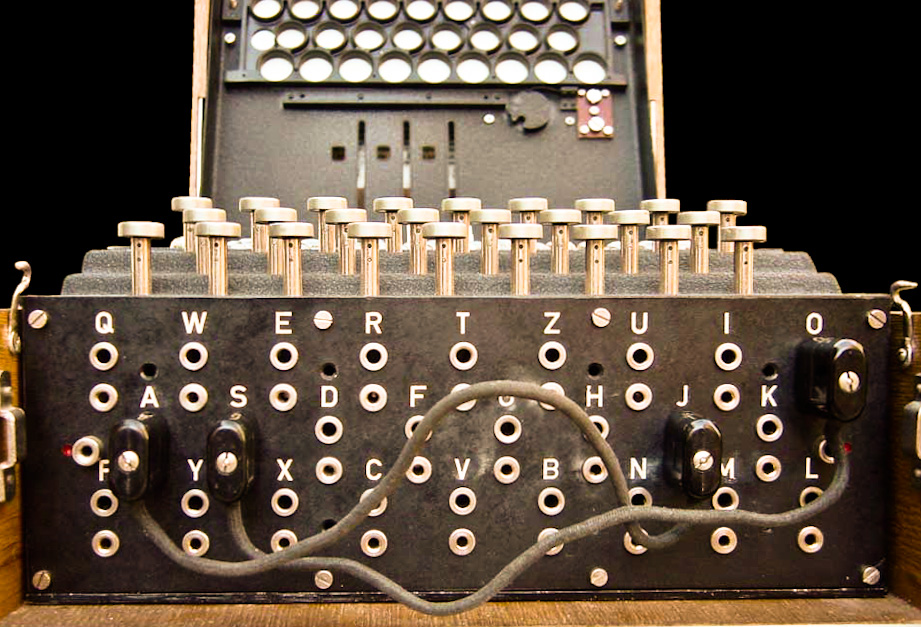

The Imitation Game is the story of this man who did what no one thought was possible; breaking the Nazis’ Enigma code during World War Two. Brilliantly played by Benedict Cumberbatch, Turing’s social awkwardness is revealed during his school years as he is bullied by his peers. It is during these years that he also strikes up a close friendship with fellow student, Christopher, a friendship that also reveals Turing’s homosexual orientation.

The team of codebreakers at Bletchley Park (where Turing built his magnificent machine) have become famous in the last decade or so for their contribution to winning the war, but it is Turing himself who is the hero of this story. This is a wonderful tale of how it is not always those who we think will be the heroes who actually are. The heroes are often those considered most unlikely by the majority.

The wisdom of the world is often foolishness to those who live in reality. And so it is that Turing, with all his social awkwardness, his arrogance and his stubbornness, is the one who is – quite literally – the mastermind behind the shortening of the war.

This movie also highlights many ethical dilemmas for those who fight the good fight. Just after Turing breaks the Enigma code, he and his cohorts realise that there is a ship that is about to be bombed by the Germans in a matter of about 30 minutes. It turns out that that very ship has, as one of its passengers, the brother of one of the Turing’s colleagues who helped break the Enigma code.

The obvious solution is to notify the Allied authorities to get the ship out of the danger area so it will not be sunk. Turing though thinks otherwise. The reason becomes clear in the movie, but it is a poignant moment which highlights the fact that issues of morality and ethics become much more than mere issues when someone we know is right in the centre. When they become personal, then principles suddenly seem a bit cold.

It is this very problem that occurs with the revelation of Turing’s homosexuality. Whatever our views on homosexuality, they seem to change when there are people we know who have a homosexual orientation. If we have any compassion, it is then no longer merely an issue. It is no longer distant; it hits much closer to home because it is now about someone’s life. It is in situations like this that we see that Christian faith is not about principles but about love.

And so it is that this movie highlights the tragedy of Alan Turing’s life. Forced to go onto hormonal therapy to “cure” his homosexuality, the full extent of the inner torment that Turing faced is distressingly revealed at the end of the movie. The man who saved 14 million lives and shortened the war by two years ends up taking his own life at the tender age of 41 because he can no longer cope with the demonisation he is forced to endure because of his sexual orientation.

Sadly there are Christians today who will still demonise the Alan Turings of this world over their sexual orientation, while conveniently overlooking the fact that he saved the lives of 14 million people.

It is those who are not considered normal by the world who God uses to perform the greatest acts of love. As Turing’s close friend Joan Clarke (played elegantly by Keira Knightley) affirms towards the end of this excellent movie,

“No one normal could have done that [broken the Enigma code]. Do you know, this morning… I was on a train that went through a city that wouldn’t exist if it wasn’t for you. I bought a ticket from a man who would likely be dead if it wasn’t for you. I read up on my work… a whole field of scientific inquiry that only exists because of you. Now, if you wish you could have been normal… I can promise you I do not. The world is an infinitely better place precisely because you weren’t.”

And, as St Paul so brilliantly says, “now these three remain: faith, hope and love. And the greatest of these is love”. When we see love in the Alan Turings of this world, rather than abnormality and oddness, we will all better reflect the image of God in which he was made.

I’ve been a Christian for 30 years. People know me as a Christian. Most of my friends are Christian. For a long time, being Christian has been my very identity. And that is a problem.

I’ve been a Christian for 30 years. People know me as a Christian. Most of my friends are Christian. For a long time, being Christian has been my very identity. And that is a problem.