This morning I preached my God is a materialist sermon at my church (North Ringwood Uniting). Click here to listen to it. The audio has a few minor changes to the original transcript, which is in 3 parts and can be found here, here and here.

Category: Meaning (Page 5 of 6)

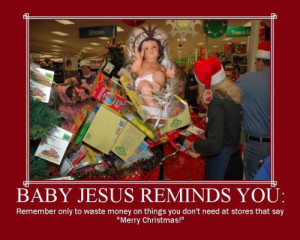

I’ve shared at different times about the insanity of how rushed we are in December each year in the lead-up to Christmas. It’s sadly ironic that the time of Advent – which covers most of December – is designed to be a time of reflection when we have turned it into the most stressful time of the year.

I’ve shared at different times about the insanity of how rushed we are in December each year in the lead-up to Christmas. It’s sadly ironic that the time of Advent – which covers most of December – is designed to be a time of reflection when we have turned it into the most stressful time of the year.

Having time to sit and reflect is good for our emotional and mental health, as well as our spiritual health. We are more rounded, whole people when we spend time doing these things. And we are invariably happier as well. The fact in Australis is though that, as a nation, we spent $8billion on Christmas and $14billion on post-Christmas sales.

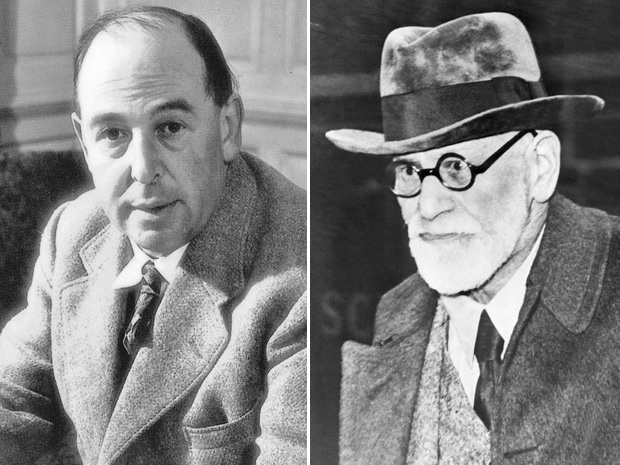

Armand Nicholi, in his book, The Question of God, brings to life an imaginary debate between two of the great minds of the 20th century, Sigmund Freud and C.S. Lewis. Here is what they both say about ethics and morality:

“Freud, however, asserts that ethics and morals come from human need and experience. The idea of a universal moral law as proposed by philosophers is “in conflict with reason.” He writes that “ethics are not based on a moral world order but on the inescapable exigencies of human cohabitation.” In other words, our moral code comes from what humans find to be useful and expedient. It is ironic that Lewis contrasted ethics with traffic laws; Freud wrote that “ethics are a kind of highway code for traffic among mankind.” That is, they change with time and culture.

…

Lewis points out that although the moral law does not change over time or from culture to culture, the sensitivity to the law, and how a culture or an individual expresses the law, may vary. For example, the German nation under the Nazi regime obviously ignored the law and practiced a morality the rest of the world considered abominable. Lewis claims that when we assert that the moral ideas of one culture are better than those of another, we are using the moral law to make that judgment. “The moment you say that one set of moral ideas can be better than another,” Lewis writes “you are, in fact, measuring them both by a standard, saying that one of them conforms to that standard more nearly than the other . . . the standard that measures two things is something different from either. You are in fact comparing them both with some Real Morality, admitting there is such a thing as a real Right, independent of what people think, and that some people’s ideas get nearer to that real Right than others.” Lewis concludes that “if your moral ideas can be truer, and those of the Nazis less true, there must be something— some Real Morality— for them to be true about.”

This is the final in a 3-part series on how many – if not most – Christians have a deficient view of heaven and of what our eternal destiny is.

This is the final in a 3-part series on how many – if not most – Christians have a deficient view of heaven and of what our eternal destiny is.

This is where the Gospel touches something deep within us, something that tells us that there really is hope, that what we are doing really is worthwhile in the end, that there really will be a day when everything will be put right. And it is not a hope in the sense of ‘gee I hope it happens.’ It is a hope based on historical fact. If we don’t believe that, it would ultimately be empty and unfulfilling and wouldn’t be real hope.

If God hasn’t come to earth in the physical person of Jesus, and if that Jesus wasn’t physically resurrected, then nothing really matters. We can make our own meaning and do all we can to bring justice while people are here. But if deep down we still know that it is not everlasting – that in the end everyone still dies and rots in the ground – then there is ultimately no justice, and no hope, and we come back to this sort of philosophy of a Richard Dawkins which says,

“In a universe of blind forces and physical replication, some people are going to get hurt, others are going to get lucky, and you won’t find any rhyme or reason in it, nor any justice. The universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil and no good, nothing but blind, pitiless indifference.”

Another Richard, Franciscan priest Richard Rohr, says that the human soul can live without success but it can’t live without meaning. Deep down we all crave significance. We all want to be part of something that matters, something that lasts. Rohr quotes Albert Einstein who said,

“The only important question is this: Is the universe friendly or not?” Can it all be trusted? Is the final chapter of history victory and resurrection or a dying whimper?”

This is the third and final of my reflections on 9/11. The first one is available here and the second is here.

This is the third and final of my reflections on 9/11. The first one is available here and the second is here.

Christian faith is about hope, that goodness really does prevail. As Martin Luther King said, the moral arc of the universe is long, and it bends towards justice. I have to ask myself, do I really want life? Or do I want a counterfeit that promises the world but leaves me more empty than before?

It has been said by many people that God is more interested in our character than our comfort. In Wrecked, Jeff Goins writes:

“People who allow their hearts to be broken for the brokenness in the world have something that most of us don’t. Compassion. Selflessness. Freedom. They “get it” in ways that most of us would find envious. There is a distinct clarity of purpose and calling in their lives that is astounding. In the face of suffering, they somehow have learned to shed their narcissism in exchange for a more meaningful life. It is incredibly brave and inspiring.”

He continues by talking about the necessity of pain if we are to really live:

“We cannot become who we are without going through pain. And who can do such a thing without trusting the struggle is worth it? Or that the results will be good? We must endeavour to be wrecked with a deep, reckless faith that confounds the world and maybe even puzzles us at times. It will be worth it.”

Here is a great little clip from Mark Sayers on why many Christians, and almost everyone in the West, have become enslaved to our feelings. I lived like this for years. For me, the old ‘fact, faith, feelings’ train in a Christian tract that I saw about 30 years ago still holds true.

[vimeo http://vimeo.com/41128426 ]

This is the second of my reflections on 9/11. The first one is available here.

Study after study has shown that money does not make us happy, and, in Australian society, once you own more than about $100,000 any amount over that won’t increase your happiness. Yet despite this we are still offered, and we still enter, lotto draws that offer such incredible amounts of money, believing that ‘life could be a dream.’ And studies show that lotto draws are becoming more popular among Australians. If this is not addiction then I don’t know what is.

The first of the Twelve Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous says ‘we realised were powerless over alcohol and that our lives had become unmanageable.’ For the addict, the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result. The thing we are doing over and over is trying to get rich, and the different result we are expecting – which goes against all the evidence – is that it will be different for us. If our culture was in a 12 Step program, we wouldn’t be at Step 1, which is the acknowledgment that we have a problem. We are a culture in denial. As well as the fact that study after study shows that money doesn’t make us happy, we now know that since the end of the Second World War, the rate of depression in Western countries has risen tenfold. Materially we are the richest people in the history of humanity, and we have ten times the rate of depression to show for it.

But as I mentioned above, don’t misunderstand this. This is about finding life, not making us all feel guilty and miserable. Jesus came to give us life and life in all its fullness. It’s about a better way, a way that is life-giving, but not the way we are told is life-giving. The way that really is life-giving often feels like the way to unhappiness and death.

Over the next 3 days I will be reflecting on the 11th anniversary of 9/11. The events of that terrible day reveal some fascinating insights into our Western contradictions, hope, happiness and what really matters in life. Today’s post is called ‘The Last Days of Mohamed Atta’ (Atta was of course one of the hijackers).

In his latest book, The Road Trip that Changed the World, Mark Sayers talks about the contradictions we all live with. He uses the very revealing example of the 9/11 hijackers and their exploits in the days before they slammed planes into icons of what they saw as Western decadence. Here is what Sayers says:

[vimeo http://vimeo.com/40927169 ]

The extraordinary actions of the hijackers highlights for me, not just the contradictions of our lives, but the confusion and deception we all buy into, whether or not we are aware of them (and mostly I don’t think we are aware).

All humans want to be happy. To quote an unlikely source – current Collingwood AFL coach Nathan Buckley – we all want to feel good. And our culture drums the message into us that a certain type of lifestyle will bring us the happiness we all crave. As M. Scott Peck said, we are people of the lie. In this case it is the lie that possessions will fill the void within.

In The Road Trip that Changed the World, Sayers goes on to talk about the consumer Christianity which has become so dominant in The US and in Australia. Relevant Magazine recently had an article questioning whether or not we would still follow Jesus if your life didn’t get any better. Here is a penetrating quote from the article:

“If we’re not careful, we inadvertently imply that if one only focuses enough on Jesus, one’s circumstances will get better, and better, and oh-so infinitely better.” This is the subtle promise of much Christianity today. If it is not straight out prosperity teaching, where the idea is that God has a plan for you to be fabulously rich and beautiful, then it is something more subtle where the idea is that God will ‘bless’ you when you serve him. And ‘blessing’ implies that things will go well for you.”

This is the third of a 2-part series on ‘What is the Gospel?’ Read part 1 here and part 2 here.

This is the third of a 2-part series on ‘What is the Gospel?’ Read part 1 here and part 2 here.

Eternal life is not having a never-ending party – the great U2 concert in the sky. N.T. Wright uses a good analogy to illustrate the wrong thinking we have about heaven and eternal life and its idea of everything being ‘perfect.’ He tells the story of a keen golfer who died and went to heaven. When he got there he got his golf clubs out and teed off on the first hole and straight away got a hole in one. He couldn’t believe it. This was amazing! He finished his round and came back the next day and this time he got a hole in one on the first and second holes. He was ecstatic. Heaven was great! The next day he got holes in one on the first 3 holes, and eventually he was going around the course in 18 shots, getting holes in one every time he played. He soon realised though that this was all rather boring.

Yesterday we started looking at what the Gospel is. Today we continue by looking at how we have reduced the Gospel to salvation only, and a wrong theology of salvation at that.

Yesterday we started looking at what the Gospel is. Today we continue by looking at how we have reduced the Gospel to salvation only, and a wrong theology of salvation at that.

Our faith has been reduced to an escapist fire insurance that has nothing more to say to the issues that face the ordinary person in the street. When it is all about going to heaven when you die, there is no ultimate concern with issues of justice, caring for the environment, and politics. Too many Christians still believe that “helping the poor is good but if they’re all going to end up in hell, what is the point? Surely the most important thing is to secure their eternal destiny. That is what really matters in the end. The other stuff is just temporary.”

The problem with this type of thinking is that it is just not biblical. And because the Bible reveals a God who addresses every aspect of life, this type of thinking can also lead to tragic consequences. Take the case of Rwanda. At the time of the 1994 genocide, this central African country was 94% Christian. So how could a country where almost everyone identifies as Christian let 800 thousand of its people be butchered in a matter of a few months? The reasons are complex, but research and interviews conducted there reveal that part of the reason is that the messages coming from the pulpits of Rwanda’s churches was largely about the afterlife. It had nothing to say to the issues facing the population in the here and now.