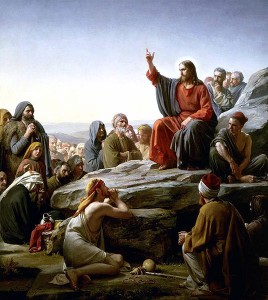

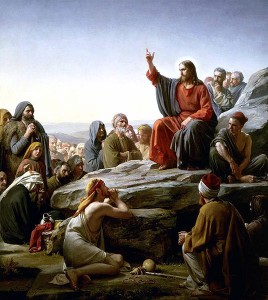

The Beatitudes, those sayings of Jesus that make up part of his Sermon on the Mount, are the heart of his teaching on the kingdom of God. But I would guess that whether you are a believer or not, you would probably have rarely, if indeed ever, have heard a sermon on these most famous of Jesus’ sayings.

The Beatitudes, those sayings of Jesus that make up part of his Sermon on the Mount, are the heart of his teaching on the kingdom of God. But I would guess that whether you are a believer or not, you would probably have rarely, if indeed ever, have heard a sermon on these most famous of Jesus’ sayings.

Throughout the 2,000 years of Christian history, there have been few people who have really taken the Beatitudes seriously as ethical guidelines. Dave Andrews offers a reason for this. He says that the Beatitudes are rarely taught in churches. And when they have been taught, more than likely people will hear that they are not to be taken literally because they are too unrealistic and can never work in the ‘real world’. This is such a common response amongst preachers that one of the most famous movie lines of all time takes it off. Check out this clip:

However when you look at the people over the years who have taken the Beatitudes literally, people like Gandhi and Martin Luther King, these are the people who have made a real difference in the world and lived the Beatitudes out in their own lives. Other people who have lived them out in different ways have been Nelson Mandela, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Vaclav Havel, Lech Walesa, and Oscar Romero.

However it is not just the Beatitudes that have been misquoted and misinterpreted. The whole Sermon on the Mount has been taken this way, to the extent that it is pretty much ignored by many Christians. There is a scene in the movie Gandhi which expresses this in a way that brings shame on the Christian church. When Gandhi meets clergyman Charlie Andrews, he asks Andrews to walk with him, and pretty soon they are both faced with a real life situation in which the reality of the Sermon on the Mount is put to the test. As they are about to walk down a laneway (remembering that this is in 1890s South Africa, when apartheid is in full swing), they are both confronted by three white young men who pour scorn on the fact that a white man is walking with a coloured man such as Gandhi. Andrews quickly suggests they perhaps go a different way, but Gandhi reminds him that the New Testament says that if someone strikes you on the right cheek, to offer him the left as well. The Christian clergyman then displays the attitude that we have seen too often in the Western church: he stutteringly tries to explain that Jesus didn’t really mean these things literally; they are more to be taken metaphorically. Gandhi though, says he is not so sure, explaining that what Jesus meant was that we must display courage, and in doing that, we will earn the respect of the oppressor but also not be pushed aside. So, as they approach the young men, the larger one tells Gandhi in no uncertain terms to get out of the neighbourhood. As he does so, he is pulled up by his mother who asks from the floor above their house what he is up to. As his mother tells the young man to get on to work, Gandhi looks him intently in the eyes and calmly exclaims, “you will find there is room for us all.”

What this exchange shows is that the Beatitudes are not some fluffy teachings of Jesus that are fine in an ideal world but can never be applied in real life. To the contrary, when lived out in the here and now, they change the world. The Beatitudes take enormous courage to put into practise. They are not to be taken metaphorically at all. Nor are they, as those on the more liberal side sometimes say, to be taken as statements by which we attain a salvation by works. Neither position takes Jesus seriously enough. And I reckon that’s why everyone knows how many commandments there are but most Christians wouldn’t know how many Beatitudes there are (there are 8).

In this scene from Gandhi, the Indian leader – the non-Christian – lives out what Jesus said. The problem for Gandhi though was that he so respected Jesus that, as John Dear points out, he could never understand why Christians didn’t obey their Master. For over fifty years, Gandhi asked Christian friends. “Why do Christians go about saying ‘Lord, Lord,’ but not do the will of Jesus? Why don’t they obey the Sermon on the Mount, reject war, practice nonviolence and love their enemies?”

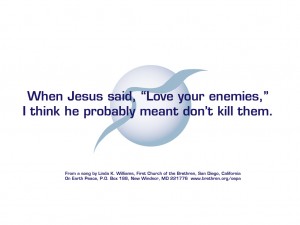

Gandhi once said that the Sermon on the Mount was the greatest teaching that has ever been given, but he decided not to become a Christian mainly because of Christians. Something else he said, which is just a great an indictment on us in the church, was that everyone knows what Jesus meant in the Sermon on the Mount except Christians. I would qualify that last statement and say ‘Western Christians’. Because for the first 300 years of the Christian church, the Sermon on the Mount was its guiding ethical framework. And look at the impact the church had in those days. It was only when Constantine became Emperor and Christianity became the official State religion of the Roman Empire and aligned itself with the powers, that it suddenly became impractical to oppose the State when it came to such teachings as ‘blessed are the peacemakers’, ‘love your enemy’ and ‘do good to those who persecute you.’ We have so lost sight of the message of the Sermon on the Mount that we now see bumper stickers like the one below reminding us of the obvious:

While there has been a shift in the church over the last 20 years or so (and the above bumper sticker was actually from a church in the US) sadly not a lot has changed since the time of Constantine. The church today generally lives by a different set of ‘Beatitudes’, as brilliantly expressed by Joe Abbey-Colborne:

Blessed are the well off and those

…with ready answers for every spiritual question;

…they have it all.

Blessed are the comfortable;

…they shall avoid grief.

Blessed are the self-sufficient;

…they wait for nothing, they have everything they want,

…and they have it now.

Blessed are those who are not troubled by

…the injustice experienced by others;

…they are content with realistic expectations.

Blessed are the ones who gain the upper hand;

…they take full advantage of their advantages.

Blessed are those with a solid public image

…and a well hidden agenda;

…they are never exposed and see people

…in a way that suits their purposes.

Blessed are those who can bully others into agreement;

…they shall be called empire builders.

Blessed are those who can point to someone else

…who is a worse person than they are,

…they will always look good by comparison.

Blessed are you when people praise you, give you preferential treatment, and flatter you because they think you’re so great. Rejoice and be exceedingly glad, because it doesn’t get any better than this.

This is the way our church has always made celebrities of the best and brightest.

As with anything like this, I need to ensure first and foremost that I am not falling into the trap of living such a smug life. The fact is that I still tend to spiritualise the Beatitudes, living as if they are good aspirations which could not work in real life. But Jesus lived them out. At the end of the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew 7, it says that the crowds were impressed with his teaching because he taught as one who had authority. That means they saw that he lived out what he taught.

So let’s have a look at these troubling sayings of Jesus:

Blessed are the poor in spirit – This one has had a few different interpretations over the years. It is one of the main ones we have tended to ‘spiritualise’ because Matthew’s version adds ‘in spirit’ whereas Luke’s version just says ‘Blessed are the poor’ (Luke 6:20). This beatitude has generally been seen to be referring to those who see themselves as inadequate, whose only hope is in God. And the fact is that these ones are actually the outcast. Listen to what Athol Gill says about this:

“For Jesus…the kingdom of God belongs especially to the poor, the powerless, the outcasts, and the dispossessed – all those who have no standing within the community. Those who count for nothing in the eyes of their fellows are the very ones to whom the kingdom of God is promised. They come empty-handed, with no power or position of their own. Their only hope is in God, and that hope will not go unrewarded.”

So it happens that the poor in spirit are also the outcast and marginalised, those with no power or privilege. And these are always the materially poor. But notice that Jesus is not saying they are blessed because they are poor. This is not about having a poverty mentality. There is no glory in wanting to be poor, UNLESS God has specifically called you to a life of poverty. They are blessed because even though they are poor, in the kingdom of God they are loved.

Blessed are those who mourn – Dave Andrews points out that God does not bless those who are happy with the present state of affairs. He blesses those who mourn. Ridley College lecturer Dave Fuller talked once about having a holy dissatisfaction with life. You don’t have to look very hard at the world to see that things are not good. Deep down we all have a sense that something is wrong with everything.

Blessed are the meek – The main thing we need to keep in mind here is that meek does not mean weak. Being meek in Jesus’ day actually referred to the taming of a wild stallion, meaning those who have powerful emotions but who have them under control. This can mean channeling your energy in surrender to God and God’s will, not being out of control and running your life how you think it should be run.

Blessed are those who seek righteousness – This should really be translated those who seek justice, as that is what the original Greek translates to, but I think both fit, because righteousness can be seen in an individual sense which is like being pure in heart, but justice is seen more in terms of social justice. Jesus sought out justice for those who were being oppressed by the Romans and the religious leaders. He said they were of the same status as everyone else. And those who seek justice in the same way as Jesus did are blessed.

Blessed are the merciful – Jesus says blessed are those who seek justice (previous beatitude) but many who are into social justice are merciless. There is a constant anger about them. I’ve seen them at peace marches. There is not a lot of gentleness shown by these people at these marches. More problematically though, I see it in myself. I very quickly become resentful at politicians who go against what I think is right. But Jesus says ‘blessed are the merciful.’ Justice and mercy are often linked throughout the Bible. An example is another classic passage from the Old Testament, Micah 6:8 – do justice, love mercy and walk humbly with your God.

Blessed are the pure in heart – This beatitude refers to those who work for what is right but don’t bring attention to themselves. I saw a coffee mug once that had written on it, ‘integrity is doing what is right when nobody is watching.’

The pure in heart are those who want to be pure, not just in their actions, but in their thoughts as well. That’s why Jesus told the disciples and the crowds to not just not kill people, but that anyone who hates has done the same thing as kill their enemy. Jesus actually intensified the norms of the culture to their true meaning. It is about integrity. That’s why he also said that when you give, don’t let your left hand know what your right hand is doing, and when you pray, go into your room and lock the door, because God sees what you’re doing. It’s not about showing everyone how righteous you are.

It needs to be pointed out here too that the Beatitudes are very confronting statements. To say in this case that purity is what’s on the inside was a profoundly politically subversive statement to make by Jesus. For to say that purity is a matter of the heart was to deny that it is a matter of observing the purity system that the religious leaders obeyed in those days. The purity system was a strict code designed to exclude ‘outsiders’. It was all about how good you looked. But Jesus turned that right around and said that it is actually about what you’re like on the inside. And the Pharisees didn’t like that one bit because they knew that he was saying to them that they were rotten on the inside. I need to constantly be aware of this to ensure that I am not being a ‘Pharisee’ myself in my own life by doing apparently godly things which actually exclude others.

Blessed are the peacemakers – This is another beatitude that Dave Andrews has some good points to make on. He explains that Jesus says that only committed peacemakers have a legitimate claim to be called children of God. And notice too that it is not saying ‘blessed are the peace keepers’; it is blessed are the peace makers; those who actively and intentionally work for peace between people. Teachings like this highlight loudly and clearly that, even under the ‘just war’ principles put forward by Ambrose and Augustine when Christianity became the State religion, our current wars simply do not fit that criteria (are you beginning to see how the Beatitudes are relevant to the real 21st century world?).

Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake – It is very important to note that this beatitude does not say ‘blessed are the persecuted’. There is no merit in suffering for suffering’s sake. It is about suffering for doing what is right, as Peter says in his letters later on in the New Testament. Just as I mentioned before that it is not about having a poverty mentality, it is also not about having suffering mentality or a martyr complex.

If we are to take the Beatitudes seriously, these sayings of Jesus call us to change ourselves. Dave Andrews says that ‘to quote the Beatitudes is religious, but to act on them is revolutionary’. Before calling on others to change, we have to change, ourselves. As we live them out, we change. The Beatitudes are about conversion – conversion to the way of Jesus. This is why the earliest Christians were called followers of the Way, because they lived out the way of Jesus, and literally thousands joined their ranks because they saw that these people were different. They cared when others didn’t. They were prepared to suffer for what was right, and they took outrageous risks of love when others didn’t.

The Beatitudes are the framework of the Sermon on the Mount, and the Sermon on the Mount is the framework of Jesus’ teaching about the kingdom of God. Remember that Jesus talks about the kingdom of God 110 times in the gospels, and he talks about being born again twice. Just something to remember for those of us who go on and on about the need to be born again while not stressing the real message of Jesus (and here I must stress that I am NOT denigrating being born again. I believe in the new birth. It is essential for a relationship with Jesus. And while Jesus mentioned it only twice, the fact is he did mention it and therefore it is to be taken very seriously. I am just saying that if we are to truly follow Jesus, we need to stress the kingdom of God much more than being born again, just as Jesus did).

In Jesus the kingdom of God has come into history. The Beatitudes are Jesus’ announcement of this coming kingdom, a time when those who mourn will be comforted, when those who hunger and thirst for justice will finally have found what they are looking for, to quote the U2 song, and when the merciful will receive mercy.

This is the upside down kingdom, when the first will be last and the last will be first (Luke 13:30), a kingdom which will finally be consummated, as we have described in that wonderful passage in Revelation, when the final coming together of heaven and earth happens and there will be no more tears or pain or death (Revelation 21:1-5). That is when all things will be made new. But here in Matthew’s gospel, with the coming of Jesus, the kingdom of God has broken into history and that is what Jesus is announcing in the Beatitudes. In him, in his life through his works of compassion, his healing, his including of those who have always been excluded, the kingdom has come. It has broken into history through this man.

So the Beatitudes are not about us. They are not just a set of values. They are about Jesus and who he is and what he is doing. This is the good news, that you who are broken, you who are last now, you will be first. It is the great reversal, and it has begun to happen in Jesus. It is the beginning of heaven coming to earth, which we see finally completed in Revelation 21 when heaven and earth come together fully and completely, never to be separate again, to make God’s consummated kingdom, where the characteristics of this kingdom reflect the character of the king – just, loving, peace, reconciling and restoring. These are all what God is like, and so it will be what life in the kingdom is like when it will finally be completed at the end of all things.

In Jesus the future has arrived; it is here. Remember that Jesus says ‘blessed ARE the poor in spirit’, not ‘blessed will be’; ‘blessed ARE you who mourn’, not ‘blessed will be’. You are blessed now, but it is not the type of blessing we often refer to in our churches. It is the blessing of the kingdom of God, of following Jesus and being drawn closer to Him. The kingdom has come, and we are called to live by its values, reflecting the king, being merciful, doing justice, loving our enemies, and living with integrity – being pure in heart, not just in outward appearance. We live like this in anticipation of the day when all things will be made new, when our hope will be made complete, when justice reigns, when peace reigns, and when love reigns, in our hearts, in our thoughts, and in the world. Amen.